What are they?

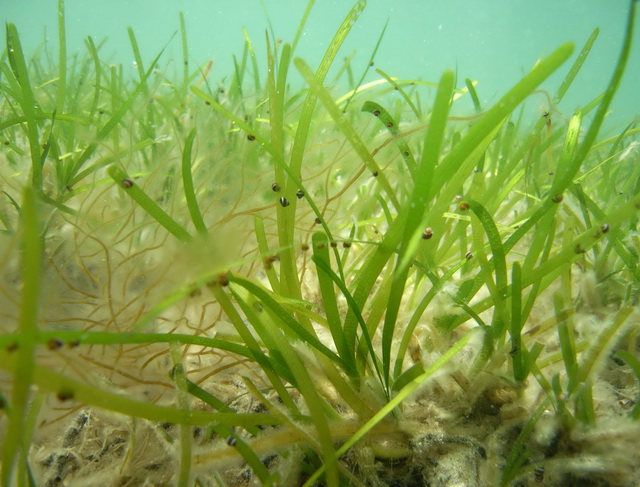

Exactly what they sound like, grasses that grow under water! While often mistaken for seaweed, they are actually more similar to the grass in your yard. They have roots, stems and leaves, and produce flowers and seeds, plus they need light to grow. Unlike your lawn though, they grow completely submerged in water.

Seagrass. Image: NOAA Fisheries

There are about 52 species of seagrass worldwide, growing as far north as the Arctic Circle, but around the Gulf Coast there are six. The distribution of the different species varies based on their preferred range of salinity, turbidity, and light requirements, but I’ll get into that more in the next section.

Most seagrasses produce asexually and sexually. Seagrass asexual reproduction is clonal, meaning that many of the plants in a seagrass meadow may appear to be individuals, but are actually a part of the same plant, with a network of underground rhizomes - which are like underground stems - supporting individual shoots. These shoots will all have the same genetic code too! This kind of growth is exhibited by terrestrial species such as aspen trees and blueberry bushes. Sexual reproduction occurs via pollination, but as you might imagine, there is a noticeable lack of bees under the sea, so pollination is aided by water movement; small invertebrates can help with this process as well. Seagrass seeds can be spread by water flow, but also by animals, such as fish and turtles, eating and excreting them.

Turtle feeding on seagrass. Image: NOAA

Where are they?

Seagrasses distribution is dictated by light, bottom type, and salinity requirements. Of the six seagrass species found in the Gulf, all six occur off the coast of Florida, and they are:

- Turtle Grass (Thalassia testudinum)

- Manatee Grass (Syringodium filiforme)

- Shoal Grass (Halodule wrightii)

- Paddle Grass (Halophila decipiens)

- Star Grass (Halophila engelmanni)

- Wigeon Grass (Ruppia maritima)

Most of these species are found Gulf-wide, in varying densities. Shoal grass and turtle grass are prevalent Gulf-wide; paddle grass is extensive in south Florida; star grass is common in Florida but is less common in the northern Gulf, only being found off of the Chandeleur Islands, Louisiana. You’d think manatee grass would only be in Florida, considering that’s the only place manatees can be found in the Gulf, but it also occurs in south Texas. Lastly, widgeon grass, which is common in estuaries that are heavily influenced by freshwater, is the only species that can grow in both freshwater and saline environments.

Check out the map below to see the distribution of all seagrasses in the Gulf of Mexico.

* These data were collected and synthesized by the Commission for Environmental Cooperation. More information regarding how the data were gathered is available in the report, “North America’s Blue Carbon: Assessing Seagrass, Salt Marsh and Mangrove Distribution and Carbon Sinks”. The report is available here

Role of Seagrasses in Fishery Ecosystems

Seagrasses contribute to fishery ecosystems in crucial ways, one of which is quite similar to grass planted on a hillside, they prevent erosion. The complex structure of seagrasses - with their leaves, roots and rhizomes - reduce erosion, improve water clarity, and reduce the impact of waves on shore. Seagrasses also support macroalgae, but their relationship can be tenuous; if the nutrient concentrations in an estuary are too high, macroalgal blooms can smother seagrass.

Seagrasses improve water quality for ecosystems. The root system stabilizes sediments and slows water flow, reducing the likelihood that sediment will be dispersed in the water column. Estuarine environments can be heavily influenced by runoff, and seagrasses clear up the water by absorbing nutrients from runoff, but in some regions, seagrass can do the exact opposite. In nutrient poor environments, seagrasses can release nutrients - taken up from the soil - into the water through their leaves.

Seagrasses directly impact fisheries in the form of habitat and feeding. Seagrass beds provide shelter for small invertebrates and small or juvenile fish. This protection attracts larger fish and sharks which feed on the invertebrates and smaller fish.

Snails on turtle grass. Image: NOAA Habitat

Many species managed by the Gulf Council - like red drum, spiny lobster, and hogfish (to name a few) - use seagrasses at some point in their life cycle. Often as fish grow larger, the seagrasses no longer provide adequate protection from predators, the blades of grass no longer conceal them, and they move to larger structures; these can be reefs, hard bottom areas, or even artificial reefs, depending on the region of the Gulf. Once a fish has moved to its adult habitat, it may stay there for the remainder of its life, with all of its reproduction, feeding, and habitat needs being satisfied by these larger structures. Other species, like herbivores, will use a reef as shelter at night and spend the day foraging in nearby seagrass beds (Valentine and Duffy 2006), whereas smaller, reef-associated carnivores spend time on reefs during the day and forage in seagrass at night (e.g., Burke 1995, Cox et al. 1997, Blackmon 2005). It’s these relationships that intrinsically link seagrass and coral habitats, though these interactions are most pronounced in southern Florida and the Florida Keys, where both habitats are prevalent.

Threats to Seagrasses

Seagrass coverage has declined in almost all areas of the Gulf since the 1950s; this stems from both natural and anthropogenic (human created) causes. Hurricanes, and the heavy wave action associated with them, can kill a significant proportion of seagrass beds, as was the case with Hurricane Camille which destroyed approximately 58% of the seagrasses in Mississippi Sound (Eleuterius and Miller 1976). Floods or droughts affect the amount of freshwater in estuaries, if the water becomes too salty or too fresh it can kill seagrass; as can increased sediment load or water turbidity. But these natural disturbances are much less harmful than the human activities associated with seagrass loss.

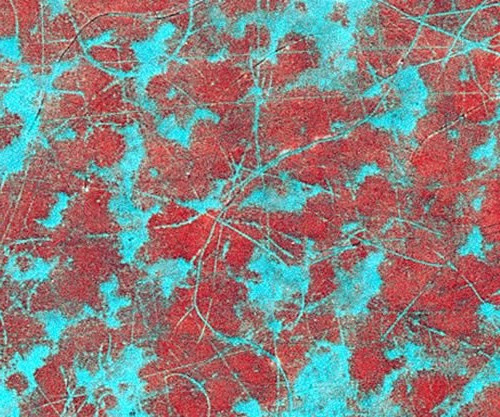

Human activities that cause seagrass loss include runoff from urban development, dredging and filling, and boat scaring. Runoff is problematic because of the pollution and nutrients entering the waterways; this is increasing with increasing coastal development. These cause turbidity and increased algal growth, which in turn reduces light penetration and causes eventual seagrass death. Coastal development and marine navigation require dredging and filling, which causes physical destruction or burying of seagrass beds. Boat scaring is caused by the propeller on a boat and is generally accidental, taking a shortcut across a channel or straying into a shallow area can result in prop scaring. The consequences of seagrass loss are numerous and can have impacts on the ecology and economy of an area.

Prop scar damage. Image: NOAA

References:

Blackmon, D.C. 2005. Diel vertical migration of seagrass-associated benthic invertebrates: a novel escape mechanism that provides and allochthonous input of seagrass-based production to coral reef resident predators. Dissertation. University of South Alabama, Mobile, Alabama, USA.

Burke, N.C. 1995. Nocturnal foraging habitats of French and bluestriped grunts, Haemulon flavolineatum and H. sciurus, at Tobacco Caye, Belize. Environmental Biology of Fishes, 42:365-374.

Cox, C., J. Hunt, W.G. Lyons, and G.E. Davis. 1997. Nocturnal foraging of the Caribbean lobster(Panularis argus) on offshore reefs of Florida, USA. Marine and Freshwater Research, 48:671-679.

Eleuterius, L.N. and G.J. Miller. 1976. Observations on seagrass and seaweeds in Mississippi Sound since Hurricant Camille. Journal of Mississippi Academy of Science, 21:58-63.

Valentine, J.F. and J.E. Duffy. 2006. The central role of grazing in seagrass ecology. Pages 463-501 in T. Larkum, R. Orth, and C. Duarte, eds. Seagrasses: biolgy, ecology, and conservation. Springer, Dordrecht, Netherlands.