What is it?

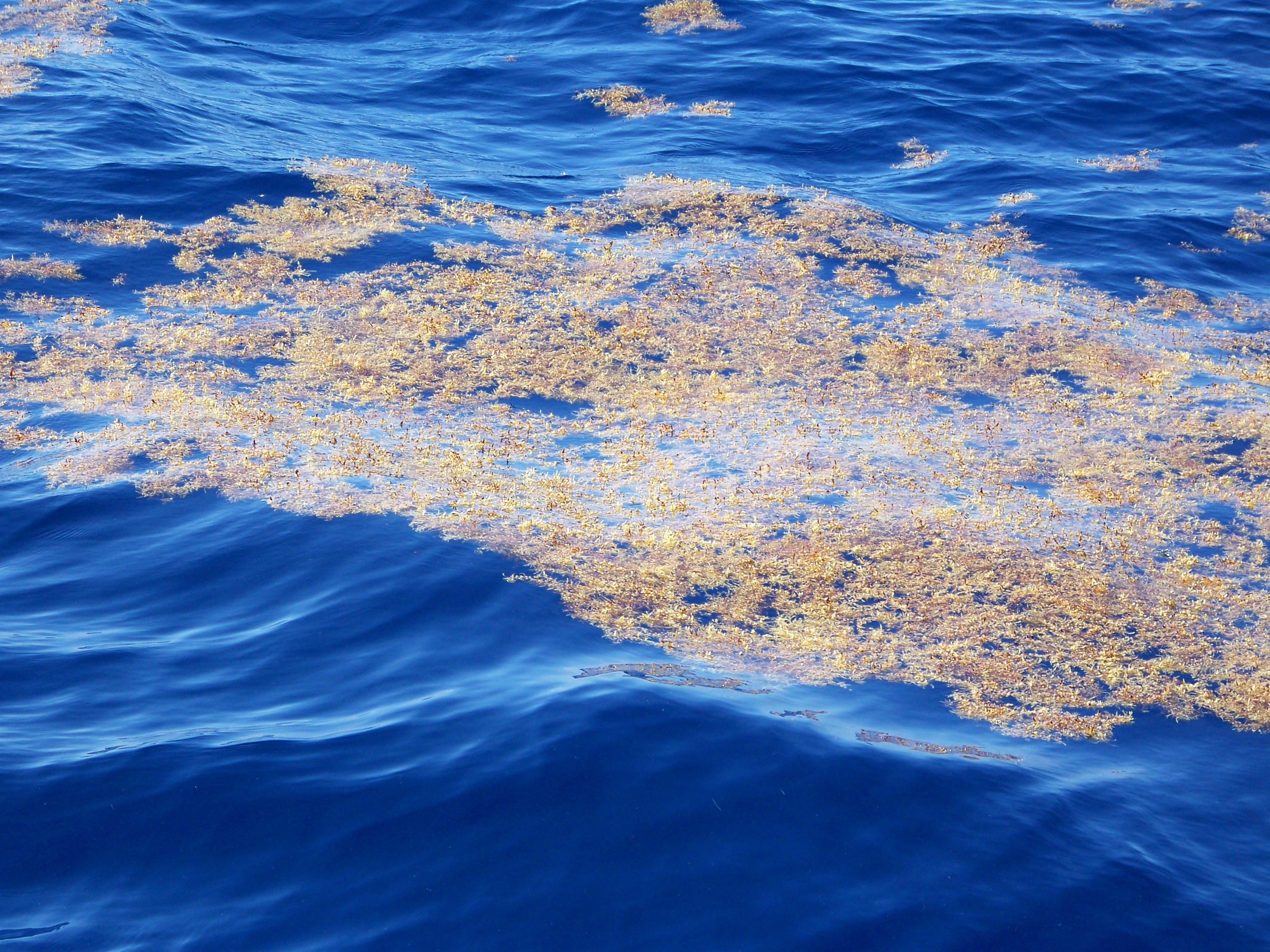

If you haven’t spent any time on a boat in the ocean, you may not be familiar with this habitat. Unlike the other habitat types highlighted on this blog, Sargassum is primarily found offshore (except when it washes ashore in huge mats, which occasionally happens in the USA).

A Sargassum line can stretch for miles across the ocean surface. Image: NOAA Teacher at Sea, Carol Schnaiter

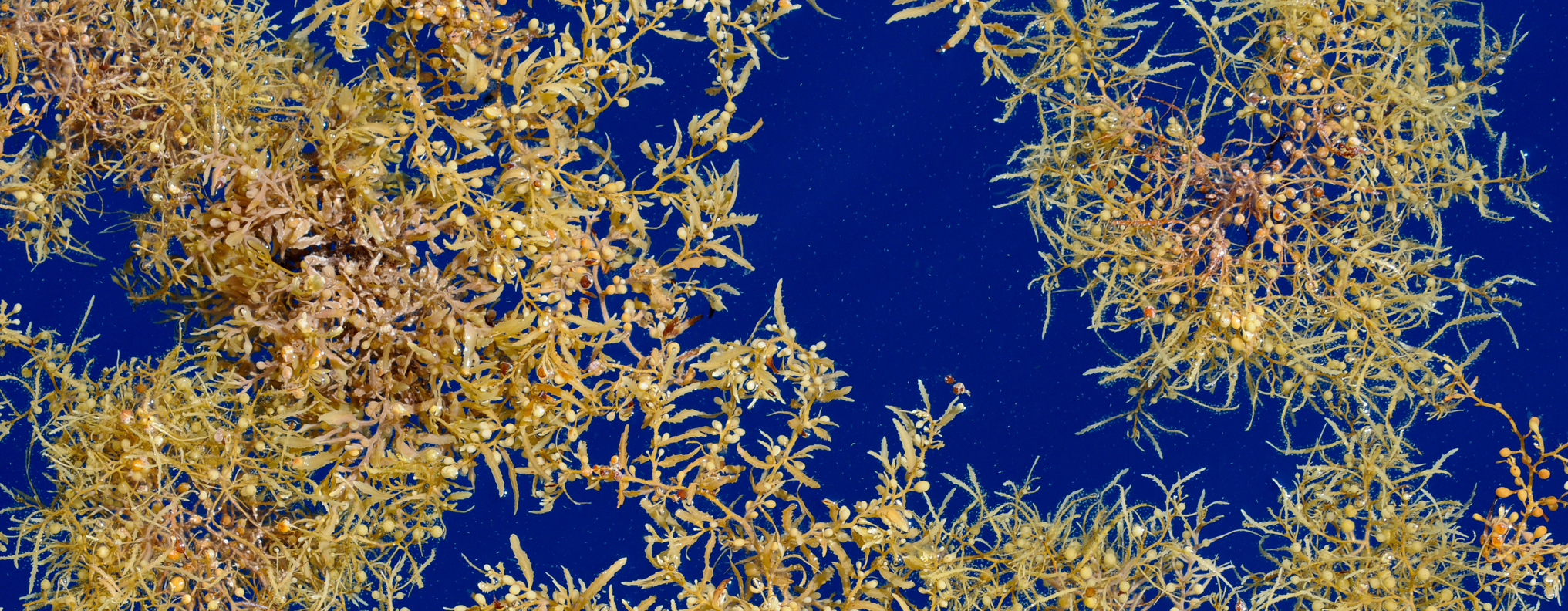

Sargassum, also called Gulf weed, is a type of large brown seaweed that floats thanks to gas-filled bladders called pneumatocysts. It can attach to rocks or reefs, like kelp but smaller, or be free-floating.

Side-by-side of kelp (left, image courtesy of NOAA Fisheries) and Sargassum (right, image courtesy of Art Howard, NAPRO).

There are two free-floating species found in the Gulf of Mexico, Sargassum natans and Sargassum fluitans. Neither species spend any of their life cycle attached to the seafloor and they reproduce solely by fragmentation, distinguishing them from all other seaweeds (Deacon 1942, Stoner 1983). During fragmentation, a younger part of the plant breaks off from the rest of the plant and eventually develops into a mature, fully grown individual. Mosses reproduce via fragmentation, as do some cacti if they lose a a stem segment. Most Sargassum has a life span of a year or less, dying off in winter and being replenished the next year (Gower and King 2011).

Where is it?

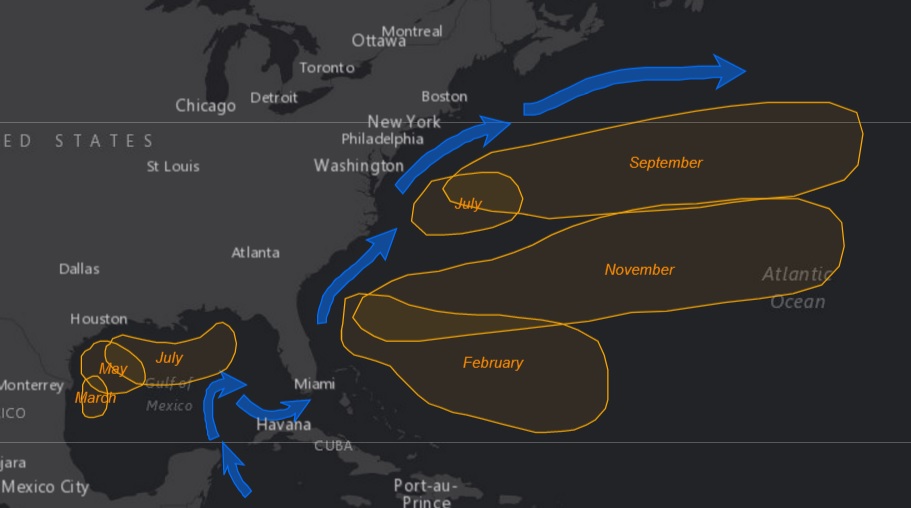

Good question! But a tough one to answer. Satellite imagery can provide snapshots in time of the distributions of Sargassum, but because its location is heavily influenced by wave, current, and wind action, Sargassum mats are always on the move. Such satellite imagery has been analyzed and data suggest that the northwest Gulf of Mexico may act as a major nursery area between March and June, before the Sargassum is funneled out of the Gulf into the Atlantic in July (Gower and King 2008).

Seasonal distribution of Sargassum.

* This map is available in a story map produced by GRID-Arendal which can be found here

Scientists are working on modeling the anticipated location of Sargassum in an effort to prepare decision makers for beaching events. Sargassum Watch System, the culmination of some of this work, uses satellite data and numerical models to track Sargassum. Sargassum tracking is almost real time, and is available here.

Role of Sargassum in Fishery Ecosystems

The open ocean is a pretty barren place, offering very little protection for larval and juvenile fishes that live in the water column, which is where Sargassum comes into play. Sargassum provides shelter on the surface of the ocean for about 120 species of fish and 120+ species of invertebrates. Gray triggerfish are an important Gulf of Mexico reef fish and really depend on Sargassum. While the adults are caught on reefs, juveniles spend anywhere from four to seven months in the pelagic environment, using Sargassum as protection from predators (Simmons and Szedlmayer 2011).

Greater amberjack, like gray triggerfish, is a commercially and recreationally important reef fish in the Gulf of Mexico. This species has been overfished since 1998 and, despite extensive management measures, has not successfully rebuilt. Larval and juvenile greater amberjack depend on Sargassum as habitat (Wells and Rooker 2004) and, given their overfished status, protecting any habitat critical to their survival and growth is particularly important.

Small fishes living in the Sargassum. Image: NOAA.

Because of the juvenile fish that congregate in Sargassum mats, predators also use this habitat to feed. If you’ve done any dolphin (the fish, not the mammal) fishing you know that finding Sargassum is key to finding the fish. This is because dolphinfish eat the other small fish species hiding in the Sargassum; the same is true for tuna and other pelagic fish species. Sargassum contributes significantly to fishery ecosystems beyond being an important habitat; other ocean animals like birds, turtles, and marine mammals use it as well.

Sargassum provides essential habitat for species like turtles. Image: NOAA Ocean Explorer.

In 2011, 2014, and 2015 large amounts of Sargassum washed ashore in the Caribbean and onto some beaches in the United States; it was such a substantial event that it was reported on by Newsweek in 2015. When Sargassum shows up at your favorite ocean-front spot it looks dirty, covering up the beautiful sandy beaches and it can smell pretty bad when it bakes in the sun. But it’s important to remember that such material can provide nutrients to beaches and can even help protect land by strengthening sand dunes.

Sargassum on the beach. Image: David Horner, NPS

Threats to Sargassum

Sargassum, like other habitat types described in this blog, is threatened by natural and human-caused degradation. Extreme weather events like hurricanes can break up Sargassum mats, cause them to strand on beaches, or sink altogether. Habitat fragmentation or disappearance entirely can be very problematic for species that depend on Sargassum in an otherwise structure-less environment.

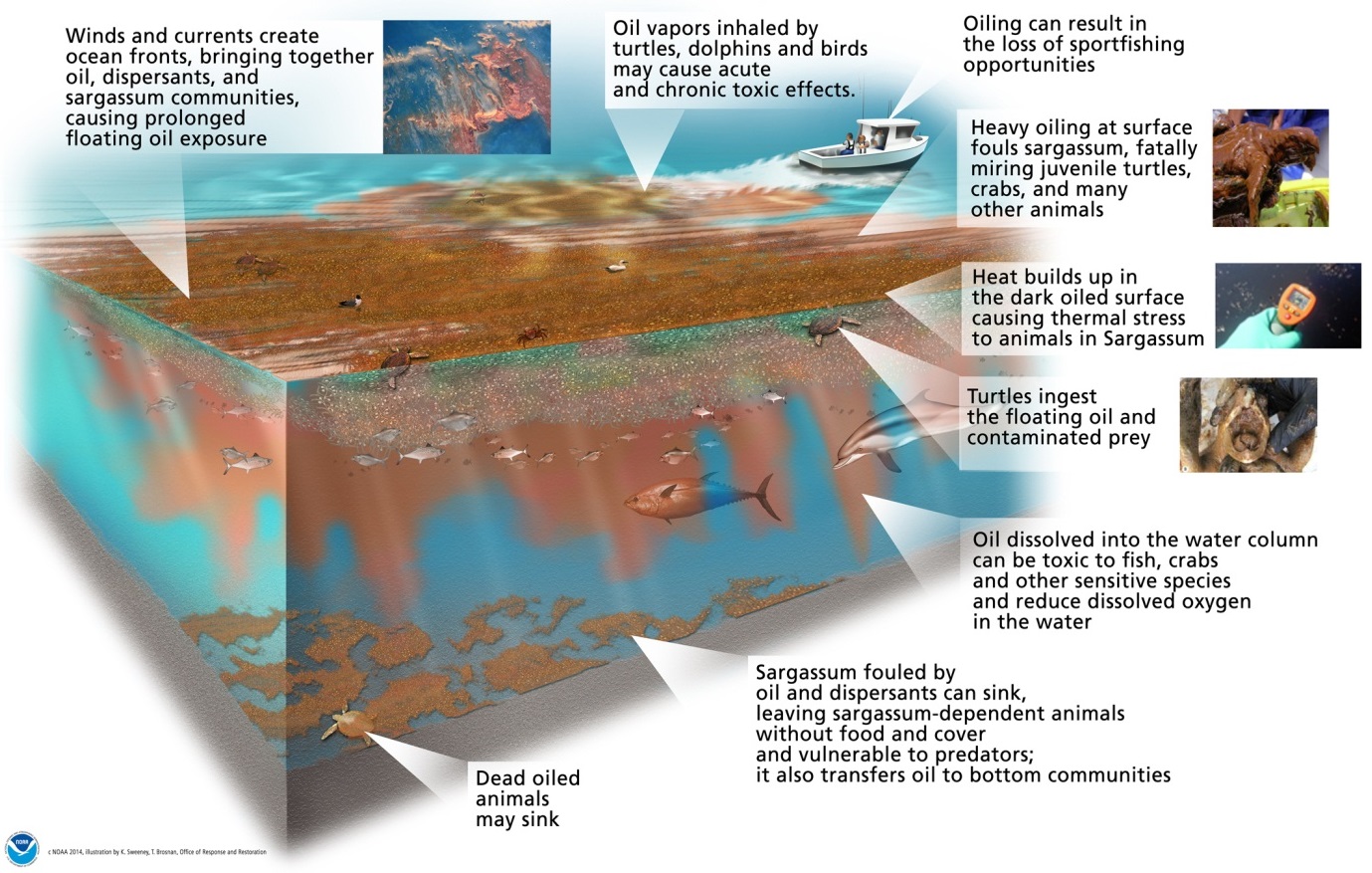

Anthropogenic (human-caused) threats to Sargassum are numerous and include obvious things like pollution, but also some disturbances that may not immediately come to mind, like shipping traffic. For those living in the Gulf states, when you think of pollution to floating habitat, an oil spill is probably your first thought. When oil comes into contact with Sargassum it gets caught up in the floating mats and impacts both the Sargassum itself, and the species associated with it. The direct impacts of oil to Sargassum include restricting growth and sinking. If the Sargassum dies from prolonged oil exposure and sinks it can bring associated oil to the bottom of the ocean where it can negatively impact animals there also. Oil vapors inhaled by species on the surface (like dolphins, turtles, and birds) can be toxic, as can contact with the oil directly, whether it be dissolved or as a surface slick, which would impact animals beneath the surface as well (like fish and crabs). For more information on oil spills and Sargassum check out this post from NOAA’s Office of Response and Restoration.

Illustration of the potential impacts of an oil spill on Sargassum and associated marine life in the water column. Image: NOAA Response and Restoration

If you’ve seen Sargassum washed up on the beach or out in the ocean, you’ve probably seen garbage tangled up in it. Since most plastics float and get carried by currents, wind, and wave action, the same as Sargassum, they tend to get mixed up together. Plastic pollution is primarily dangerous for animals in the Sargassum and less so for the Sargassum itself. Up to 52% of sea turtles worldwide have eaten plastic debris, and olive ridley turtles, while not present in the Gulf of Mexico, are at particular risk because of their feeding habitats (Schuyler et al. 2016). Many species of sea turtle (including olive ridleys) eat jellyfish, and plastic bags can look very similar floating through the ocean. In addition to the harm of ingesting plastics, animals can also get caught in things like fishing nets, plastic bags or balloons.

Diver releasing a sea turtle caught in a derelict fishing net. Image: NOAA Marine Debris Program

Shipping traffic is another less obvious disruptor of Sargassum environments. Cargo and tanker vessels are common in the Gulf of Mexico and they have the potential to disrupt Sargassum communities in several ways: 1) physical disruption of moving through Sargassum mats, 2) pollutant (sewage, oil, chemicals) discharge, and 3) disruptive noise generated by the ships (Laffoley et al. 2011). More research is needed to quantify the impacts of shipping vessels on Sargassum communities.

A thorough report on threats to Sargassum is available from The Sargasso Sea Alliance and can be found here.

* This map illustrates the density of shipping vessel (cargo and tanker) traffic in the Gulf of Mexico in 2013. More information on the data used to create this map can be found here.

References:

Deacon, G. E. R. 1942. The Sargasso Sea. The Geographical Journal. 99: 16-28.

Gower, J. and S. King. 2008. Satellite images show the movement of floating Sargassum in the Gulf of Mexico and Atlantic Ocean. Available from Nature Precedings.

Gower, J. F. R. and S. A. King. 2011. Distribution of floating Sargassum in the Gulf of Mexico and the Atlantic Ocean Mapped using MERIS. International Journal of Remote Sensing, 32(7).

Laffoley, D.d’A., H. S. J. Roe, M. V. Angel, J. Ardron, N. R. Bates, I. L. Boyd, S. Brooke, K. N. Buck, C. A. Carlson, B. Causey, M. H. Conte, S. Christiansen, J. Cleary, J. Donnelly, S. A. Earle, R. Edwards, K. M. Gjerde, S. J. Giovannoni, S. Gulick, M. Gollock, J. Hallett,P. Halpin, R. Hanel, A. Hemphill, R. J. Johnson, A. H. Knap, M. W. Lomas, S. A. McKenna, M. J. Miller,P. I. Miller, F. W. Ming, R. Moffitt, N. B. Nelson, L. Parson, A. J. Peters, J. Pitt, P. Rouja, J. Roberts, J. Roberts, D. A. Seigel, A. N. S. Siuda, D. K. Steinberg, A. Stevenson, V. R. Sumaila, W. Swartz, S. Thorrold, T. M. Trott and V. Vats. 2011. The protection and management of the Sargasso Sea: The golden floating rainforest of the Atlantic Ocean. Summary Science and Supporting Evidence Case.Sargasso Sea Alliance, 44 pp.

Schuyler, Q. A., C. Wilcox, K. A. Townsed, K.R. Wedemeyer-Strombel, G. Balazs, E. van Sebille and B. D. Hardesty. Risk analysis reveals global hotspots for marine debris ingestion by sea turtles. Global Change Biology, 22(2): 567-576.

Simmons, C. M. and S. T. Szedlmayer. 2011. Recruitment of age-0 gray triggerfish to benthic structured habitat in the northern Gulf of Mexico. Transactions of the American Fisheries Society, 140(1): 14-20.

Stoner, A. W. 1983. Pelagic Sargassum: Evidence for a major decrease in biomass. Deep Sea Research, 30: 469-474.

Wells, R. J. and J. R. Rooker. Spatial and temporal patterns of habitat use by fishes associated with Sargassum mats in the northwestern Gulf of Mexico. Bulletin of Marine Science, 74(1): 81-99.